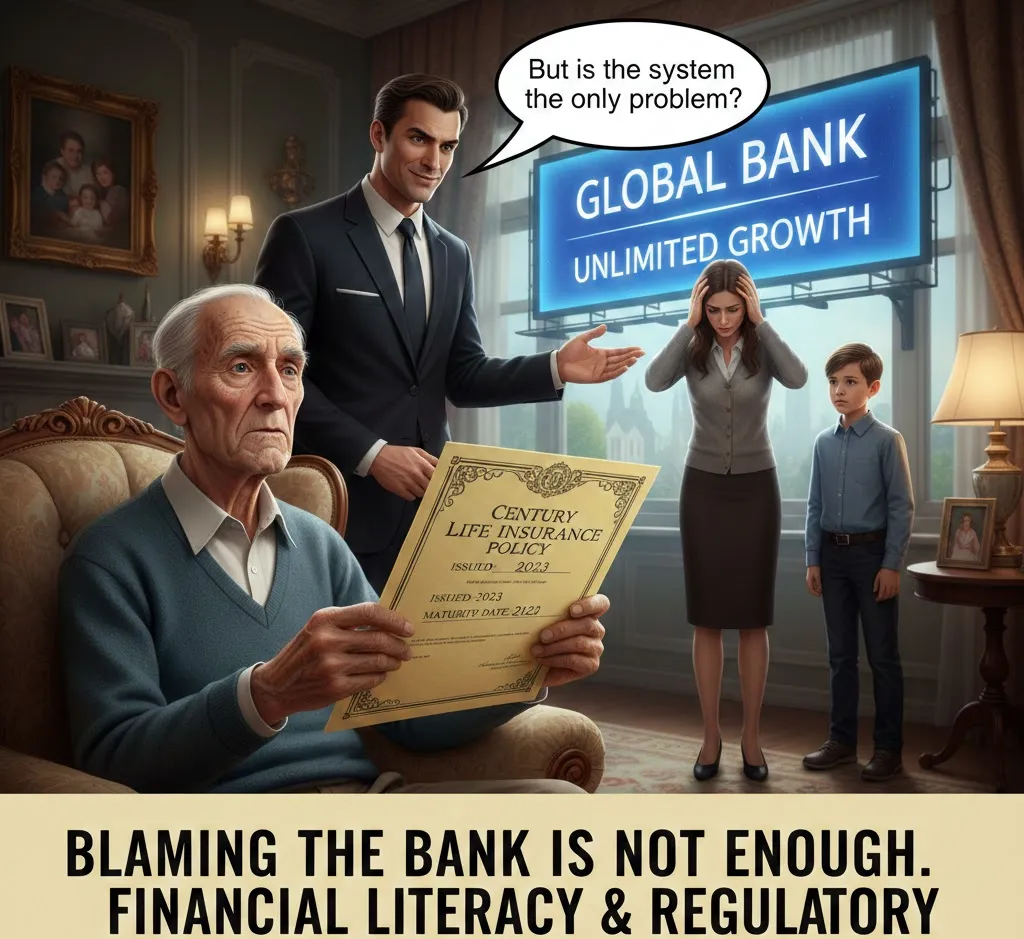

Life Insurance Sold to 90-Year-Old Sparks Debate on India’s Mis-Selling Crisis

A 90-year-old man was sold a life insurance policy set to mature in 2124 — a case that has reignited concerns about systemic mis-selling practices in India’s financial sector. The elderly customer, Venkatachalam V Iyer, was reportedly signed up for a policy with an annual premium of Rs 2 lakh. Two instalments were debited before his family discovered the issue.

The matter gained traction on social media after it was highlighted by Saketh R, who identified the customer as his wife’s grandfather and a long-time customer of the same Canara Bank branch. Following public attention, the premium amount was refunded and the family acknowledged the bank’s swift resolution.

While the immediate issue was resolved, the larger question remains: would the refund have happened without social media intervention?

Mis-Selling: A Structural Issue

The case is not an isolated anomaly. According to data from the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (IRDAI), more than 2.5 lakh insurance grievances were recorded in FY2024-25 through the Bima Bharosa system. Of these, approximately 1.2 lakh complaints related to life insurance, with over one-fifth categorised under unfair business practices such as mis-selling and improper disclosure.

This means tens of thousands of policyholders annually allege that the product they purchased did not align with what was promised.

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has acknowledged the issue, proposing draft guidelines to tighten norms around the sale of third-party financial products by banks. These proposals stress product suitability, explicit consent, compensation mechanisms, and potential supervisory penalties for violations. However, these guidelines remain in draft form.

Why Senior Citizens Need Stronger Safeguards

Experts argue that sales involving elderly customers — especially those above 60 — should automatically trigger enhanced scrutiny. Shilpa Arora, co-founder and COO of Insurance Samadhan, has recommended mandatory recorded suitability conversations, clear disclosure of lock-in periods and surrender penalties, and independent confirmation from the life insured when different from the proposer.

Such procedural safeguards, including video or audio documentation, could create verifiable evidence of informed consent and reduce disputes later. The key argument is that prevention mechanisms must be embedded in the sales process rather than activated only after complaints arise.

Incentives Over Suitability?

Mis-selling often stems from incentive structures rather than isolated misconduct. Banks earn commissions from distributing insurance products, and branch staff operate under cross-selling targets. Insurers rely heavily on bancassurance channels for premium growth. In such an ecosystem, sales volume can quietly overshadow product suitability.

If a policy is processed and issued, it has passed documentation and underwriting checks — broadening accountability beyond just the frontline salesperson. Questions arise around entry-age norms, suitability assessments, and the quality of consent obtained.

A Larger Regulatory Test

While the refund in this case brought relief, it does not address systemic vulnerabilities. A 90-year-old customer banking with the same branch for decades should not require public outrage to prompt review.

The incident underscores a broader issue: India’s financial system must realign incentives, enforce accountability, and introduce robust safeguards for vulnerable customers. Regulatory intent is visible. The real test will be consistent enforcement and meaningful deterrence.

The refund closes this case. It does not close the question of whether India’s mis-selling problem has been truly addressed.